Firstly, I’d like to thank EastSide Partnership and Heritage Officer, Lisa Rea Currie, for the opportunity to be a guest blogger.

My name is Gaynor Kane (nee Carson) and I’m from east Belfast. I went to school at Elmgrove PS and Orangefield Girl’s High. I’m a volunteer for EastSide Arts and a member of the community team working with Lisa on the ‘EastSide Lives’ project. EastSide Lives invited members of the community to research east Belfast citizens of the past and tell their stories through artwork and interpretation on a walking trail. One of the stops on the trail tells the story of my great-grandfather, James Forrester, who worked in the shipyard. Family legend states that he was asked to be part of the Titanic’s guarantee group on her maiden voyage. But! He didn’t go. You’ll have to wait for the trail to be launched to find out why.

I’ve also been writing for the last few years, since graduating with a BA (Hons) degree from the Open University (OU). I have a pamphlet of poetry, Memory Forest, which I launched in the EastSide Visitor Centre in December 2019, and a full collection, Venus in pink marble, coming this Summer, both published by Hedgehog Poetry Press.

As part of my OU Creative Writing module, I wrote a short story about the Forrester family. It is written from the point of view of the eldest child in the family, Eveleen. It hibernated in my ‘to be edited’ folder, since 2016 until recently when a writer’s group I’m a member of put out a call for stories on place and I thought it was the perfect opportunity to polish the story, ready for publication.

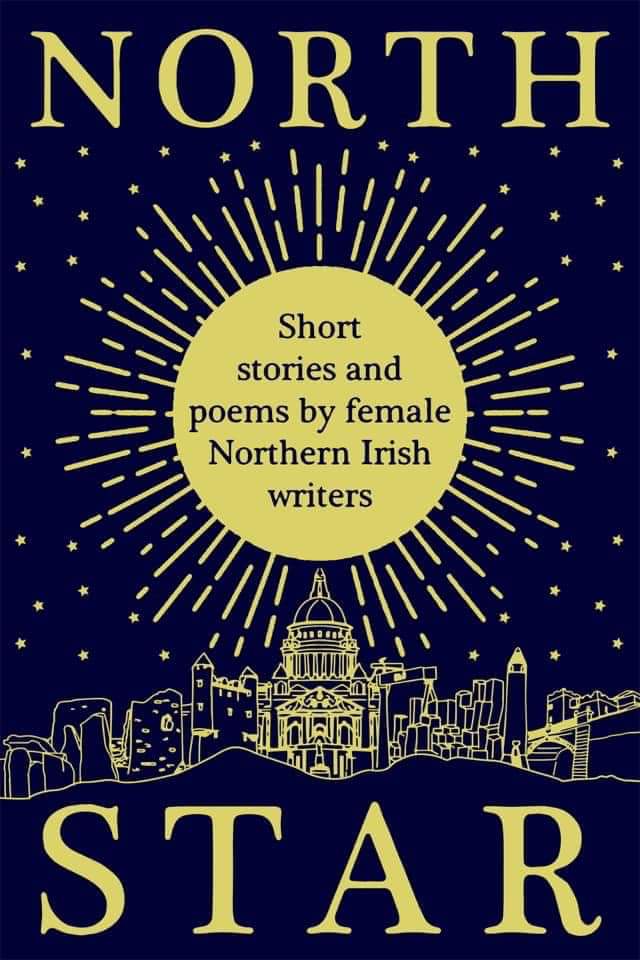

The group, Women Aloud NI, have used lockdown to curate an anthology of short stories and poems. It is entitled North Star and was the brainchild of chairwomen, Angeline King, who explains:

“It was born out of the wish to portray writers’ homeplaces – our villages, towns, cities, counties, or wherever we have found ourselves firmly rooted.”

Women Aloud NI was founded in 2016, by Jane Talbot, to raise the profile of women writers from, or living in, Northern Ireland. It does this through social media and by taking part in a number of literary festivals each year.

The book, which includes the poetry and stories of 45 women, in sections by county, from publisher Leschenault Press, is available to order now on Amazon, where you can read more about it.

Perhaps the start of my Titanic tale might whet your appetite!

A Memoir of Eveleen Forrester

The first of October 1911, on 23 Lendrick Street, Belfast.

Ma and I rose before the rest of the household, though still in our night

clothes. She put a kettle on to boil while I lit the fire and put the wash bowls on the

table. We washed in disjointed synchronicity so that neither of us required the towel

at the same time.

Ma was so heavily pregnant that each step must have been like Everest

every time she climbed the steep staircase. The gilt frame on the mantelpiece

showed a slim, handsome, young couple on their wedding day, but Ma’s breasts

had swollen with each baby, and her cheeks were plump now.

I woke the boys and my little sister, Mabel, the youngest of the family.

She’d just started school and still needed help lacing her boots. Thin soles and

uneven heels meant that the boots, previously worn by me and the boys, took all

the cobbler’s skill to hold them together.

Ma was in the scullery, kneading soda bread while the griddle smoked and

spat. It filled the house with an aroma like heavenly manna as they cooked.

‘Ted pinched me!’ squealed Mabel.

‘Teddy, don’t tease your sister.’

‘What’s in my piece today, Mother?’ Jimmy was thirteen, tall as a giraffe

but with strong legs. His appetite could never be sated.

‘Jam again, son.’

That’d be thanks to our successful blackberry picking.

‘Right, children, hurry up! Eat breakfast quickly, or you’ll be late for

school,’ Father’s English accent cut the conversation short.

‘Dreamin’ of your childhood, darlin’?’

‘How did you know that, Charlotte?’ He asked with a puzzled

expression.

Mother and I exchanged smiles. We seemed to be the only ones to

ever detect the subtle differences in his accent. My Father’s family had been in

shipbuilding for a least two generations, and his own Father had travelled the

country to different yards, building ever bigger ships. Father had adopted every

local dialect. If he’d been dreaming about his adolescence, he'd have woken up

speaking broad Glaswegian.